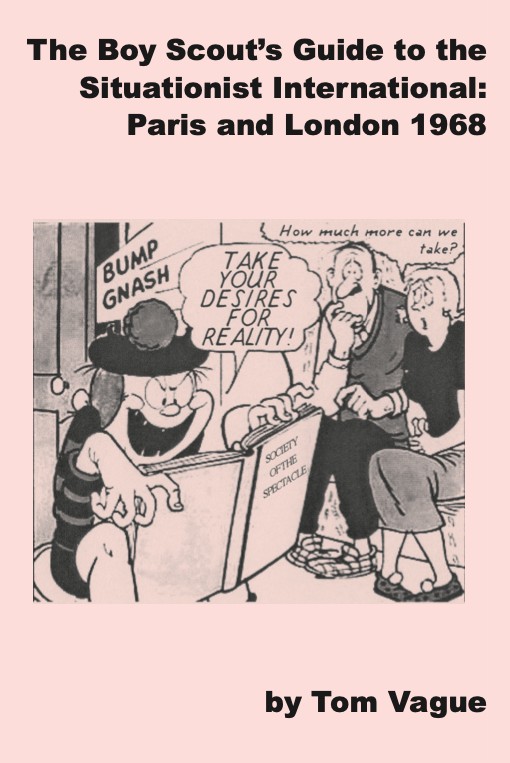

The Boy Scout’s Guide to the Situationist International A6

£1.50

The Effect The S.I. Had On Paris ’68 And All That, Through The Angry Brigade And King Mob To The Sex Pistols. New A6 pocketsize booklet reprint, Active 2021

Description

Originally printed in the notorious zine Vague (issue 49) this is Tom Vagues guide to the even more notorious Situationist International

Situationist International Definitions Constructed Situation A moment of life concretely and deliberately constructed by the collective organisation of a unitary ambiance and a game of events. Situationist Having to do with the theory or practical activity of constructing situations. One who engages in the construction of situations. A member of the Situationist International. Situationism A meaningless term improperly derived from the above. There is no such thing as situationism, which would mean a doctrine of interpretation of existing facts. The notion of situationism is obviously devised by anti-situationists. Psychogeography The study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour on individuals. Psychogeographical Relating to psychogeography. That which manifests the geographical environment’s direct emotional effects. Psychogeographer One who explores and reports on psychogeographical phenomena. Derive: A mode of experimental behaviour linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of transient passage through various ambiances. Also used to designate a specific period of continuous deriving. Unitary Urbanism The theory of the combined use of arts and techniques for the integral construction of a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behaviour.

Detournement Short for: detournement of pre-existing aesthetic elements. The integration of present or past artistic production into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of these means. In a more primitive sense, detournement within the old cultural spheres is a method of propaganda, a method which testifies to the wearing out and loss of importance of those spheres. Culture The reflection and prefiguration of the possibilities of organisation of everyday life in a given historical moment; a complex of aesthetics, feelings and mores through which a collectivity reacts on the life that is objectively determined by its economy. (We are defining this term only in the perspective of the creation of values, not in that of the teaching of them.) Decomposition The process in which the traditional cultural forms have destroyed themselves as a result of the emergence of superior means of dominating nature which enable and require superior cultural constructions. We can distinguish between an active phase of the decomposition and effective demolition of the old superstructure – which came to an end around 1930 – and a phase of repetition which has prevailed since then. The delay in the transition from decomposition to new constructions is linked to the delay in the revolutionary liquidation of capitalism.

The Society of the Spectacle and the Revolution of Everyday Life The Situationist International formed in 1957 out of the Lettrist International, a Parisian avant-garde art group who predated punk by almost 30 years in wearing trousers painted with slogans. Owing as much to Dada and the Surrealists as Marx and Bakunin, the Situationists’ starting point was the original working class movement had been crushed, by the bourgeoisie in the west and the bolsheviks in the east; working class organisations like trade unions and leftist political parties had sold out to world capitalism; and capitalism could appropriate even the most radical ideas and return them safely in the form of harmless ideologies.

In opposition to this process, the leading Situationist Guy Debord formulated his theory of the Spectacle: ‘The moment when the commodity has achieved the total occupation of life.’ Debord argued, in the Internationale Situationniste journal, that through computers, television, rapid transport systems and other forms of advanced technology, capitalism controlled the very conditions of existence. Hence the world we see is not the real world but the world we are conditioned to see: the Society of the Spectacle. Debord saw the end result as alienation, but didn’t necessarily see this as a bad thing as he felt this would eventually break the stranglehold of spectacular society. People were already rebelling against mass commodity culture; thousands of affluent young Americans had dropped out in Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco, while in the Watts suburb of Los Angeles less affluent black people set fire to shopping centres.

To the Situationists such spontaneous revolts against the Spectacle were evidence of its vulnerability. But before it could be overcome the Spectacle’s safety net, recuperation, had to be dealt with. To survive spectacular society has to have strict social control. This is retained by its ability to recuperate a potentially revolutionary situation. By changing chameleon-like it can resist an attack, creating new roles, cultural forms and encouraging participation in the construction of the world of your own alienation. For example alternative lifestyles can be turned into commodities, safely recuperated and sold back to people, inducing a yearning for the past. For those bored with the possession of mere things, the Spectacle is capable of commodifying the possession of experiences; in the form of package holidays and pop culture. Spectacular society is made complete by the recuperation of the environment. The recuperators realised that people would resist the damage the growth of the Spectacle; heavy industry and consumerism; was doing to their physical surroundings. Hence environmental recuperation or the ‘new urbanism’; replacing disordered urban-sprawl with more manageable structures, factory towns, new towns, supermarkets and shopping malls.

The Situationists’ answer to the new urbanism was the reconstruction of the entire environment, according to the needs of the people that inhabit it. Their answer to modern society was to be nothing short of the Revolution of Everyday Life (the title of the companion book to Society of the Spectacle) by Raoul Vaneigem. Unlike traditional revolutionary groups, the Situationists were not concerned with the improvement of existing society or reforming it. They were interested in destroying it and putting something new and better in its place. The Situationist programme began where art ended. They argued that mechanisation and automation had potentially eliminated the need for all forms of traditional labour, leaving a hole, now known as leisure time. Rather than fill this hole with specialist art, the Situationists wanted a new type of creativity to come out of it. This new environment has to be brought about by the construction of situations.

On the Poverty of Student Life ‘To make the world a sensuous extension of man rather than have man remain an instrument of an alien world, is the goal of the Situationist revolution. For us the reconstruction of life and the rebuilding of the world are one and the same desire. To achieve this, the tactics of subversion have to be extended from schools, factories, universities, to confront the Spectacle directly. Rapid transport systems, shopping centres, museums, as well as the various new forms of culture and the media, must be considered as targets, areas for scandalous activity.’ Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life

The Situationists first hit the headlines in 1966, when a group of pro-Situ activists infiltrated the Strasbourg University students union and set about scandalising the authorities. After forming an anarchist appreciation society, they printed up Situationist-inspired ‘Return of the Durruti Column’ flyposters, and invited the Situationists to write a critique of the university and society in general. The resulting pamphlet, On The Poverty of Student Life: Considered in its economic, political, sexual, and particularly intellectual aspects, and a modest proposal for its remedy (Ten Days That Shook The University) by the Tunisian Situationist Mustapha Omar Khayatti, was designed to wind up the apathetic students by confronting them with their subservience to the family and the state:

“The whole of (the Student’s) life is beyond his control, and for all he sees of the world he might as well be on another planet…Every student likes to feel he is a bohemian at heart; but the student bohemian clings to his false and degraded version of individual revolt. His rent-a-crowd militancy for the latest good cause is an aspect of his real impotence…he does have marginal freedoms; a small area of liberty which as yet escapes the totalitarian control of the Spectacle; his flexible working hours permit adventure and experiment. But he is a sucker for punishment and freedom scares him to death: he feels safer in the straightjacketed space-time of the lecture hall and the weekly essay. He is quite happy with this open prison organised for his benefit…The real poverty of his everyday life finds it’s immediate phantastic compensation in the opium of cultural commodities…he is obliged to discover modern culture as an admiring spectator…he thinks he is avant-garde if he’s seen the latest Godard or ‘participated’ in the latest ‘happening’. He discovers modernity as fast as the market can provide it: for him every rehash of ideas is a cultural revolution. His principal concern is status, and he eagerly snaps up all the paperback editions of important and ‘difficult’ texts with which mass culture has filled the bookstore. Unfortunately, he cannot read, so he devours them with his gaze…’

The university was described as: ‘The society for the propagation of ignorance…high culture with the rhythm of the production line…without exception the lecturers are cretins…bourgeois culture is dead…all the university does is make production-line specialists.’ Existing student rebels, such as the Dutch Provos and the Berkeley students, were criticised for fighting the symptoms (nuclear arms, the Vietnam war, racism, censorship) not the disease, and for their tendency to sympathise with western society’s apparent enemies; China especially, whose cultural revolution was described as ‘a pseudo-revolt directed by the most elephantine bureaucracy of modern times.’ It did have a good word for the Committee of 100′s ‘Spies for Peace’ scandal; in which the anti-nuclear movement invaded secret fallout shelters reserved for the British government. Away from student life, the pamphlet pointed out that working class youths were rebelling against the boredom of everyday life more effectively:

‘The ‘delinquents’ of the world use violence to express their rejection of society and its sterile options. But their refusal is an abstract one: it gives them no chance of actually escaping the contradictions of the system. They are its products – negative, spontaneous, but none the less exploitable. All the experiments of the new social order produce them: they are the first side-effects of the new urbanism; of the disintegration of all values; of the extension of an increasingly boring consumer leisure; of the growing control of every aspect of everyday life by the psycho-humanist police force; and of the economic survival of a family unit which has lost all significance. The ‘young thug’ despises work but accepts the goods. He wants what the spectacle offers him – but now, with no down payment. This is the essential contradiction of the delinquent’s existence. He may try for a real freedom in the use of his time, in an individual assertiveness, even in the construction of a kind of community. But the contradiction remains, and kills (on the fringe of society, where poverty reigns, the gang develops its own hierarchy, which can only fulfil itself in a war with other gangs, isolating each group and each individual within the group). In the end the contradiction proves unbearable. Either the lure of the product world proves too strong, and the hooligan decides to do his honest day’s work: to this end a whole sector of production is devoted specifically to his recuperation. Clothes, records, guitars, scooters, transistors, purple hearts beckon him to the land of the consumer. Or else he is forced to attack the laws of the market itself – either in the primary sense, by stealing, or by a move towards a conscious revolutionary critique of commodity society. For the delinquent only two futures are possible: revolutionary consciousness, or blind obedience on the shop floor.’

Summing up, On the Poverty of Student Life outlined the solution as confronting the social system with the negative forces it produces: ‘We must destroy the Spectacle itself, the whole apparatus of the commodity society… We must abolish the pseudo-needs and false desires which the system manufactures daily in order to preserve its power.’ Using appropriated union funds, 10,000 copies of the pamphlet were printed and handed out at the official ceremony to mark the beginning of the Strasbourg academic year. An immediate outcry ensued in which the rector of the university said the students should be in a lunatic asylum, as the local, national and international press condemned the pamphlet as an incitement to violence, which of course it unashamedly was.

One Strasbourg press report announced: ‘The San Francisco and London beatniks, the mods and rockers of the English beaches, the hooligans behind the Iron Curtain, all have been largely superseded by this wave of new style nihilism. Today it is no longer a matter of outrageous hair and clothes, of dancing hysterically to induce a state of ecstasy, no longer even a matter of entering the artificial paradise of drugs. From now on, the international of young people who are ‘against it’ is no longer satisfied with provoking society, but intent on destroying it – on destroying the very foundations of society ‘made for the rich and old’ and acceding to a state of ‘freedom without any kind of restriction whatsoever.’

The students responsible were duly expelled and the student union closed by court order, as the judge pronounced: “The accused have never denied the charge of misusing the funds of the student union. Indeed, they openly admit to having made the union pay for the printing of 10,000 pamphlets, not to mention the cost of other literature inspired by the International Situationniste. These publications express ideas and aspirations which, to put it mildly, have nothing to do with the aims of a student union. One only has to read what the accused have written, for it is obvious that these five students, scarcely more than adolescents, lacking all experience of real life, their minds confused by ill-digested philosophical, social, political and economic theories, and perplexed by the drab monotony of their everyday life, make the empty, arrogant and pathetic claim to pass definitive judgments, sinking to outright abuse, on their fellow students, their teachers, God, religion, the clergy, the governments and political systems of the whole world, rejecting all morality and restraint, these cynics do not hesitate to commend theft, the destruction of scholarship, the abolition of work, total subversion and a worldwide proletarian revolution with ‘unlicensed pleasure’ as it’s only goal. In view of their basically anarchist character, these theories and propaganda are eminently noxious. Their wide diffusion in both student circles and among the general public, by the local, national and foreign press, are a threat to the morality, the studies, the reputation and thus the very future of the students of the University of Strasbourg.”

Paris 1968 ‘This work is part of a subversive current of which the last has not yet been heard. Its significance should escape no one. In any case, as time will show, no one is going to escape its implications.’ Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life

In the following years the ideas and tactics of the Situationist International, or at least a fair bit of discontent fuelled by the Strasbourg pamphlet, spread like wildfire through the universities of France. In the mid 60s the French university system was heading for trouble anyway, largely due to overcrowding. The government tried to deal with the crisis by setting up overspill colleges in the provinces and slum-outskirts of Paris, but this only made matters worse. One of the Paris overspill colleges in particular, Nanterre, situated amidst waste disposal tips and the Spanish immigrant ghetto, was almost perfect for intervention. There was already a strong feeling of alienation amongst the students; uprooted from their former bohemian cafe lifestyle in the Latin Quarter and dumped in council flat style blocks, with separate residential buildings for males and females, no recreational facilities, everything controlled by a faceless centralised bureaucracy in Paris; it was all straight out of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle.

However Nanterre did have one of the few sociology departments in France and, at the beginning of 1968, a lot of radical students were concentrated there. After a few months of simmering discontent, a group of students drew up a list of reforms. Most of their demands were quite reasonable, like the right to specialise in subjects of their own choice, but they deliberately pressed on with claims they knew would be rejected, and all talk of reform was soon forgotten. As they used to say, be realistic demand the impossible. The students involved became known as the Enrages because of their theatrical nature and the violence of their demonstrations, in the tradition of the 18th Century revolutionary Enrages led by Jacques Roux, who ended up guillotined by the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The new Enrages began disrupting lectures, breaking down communication between lecturers and students; then escalated the disorder by spreading rumours that plain-clothes policemen had infiltrated the university campus to compile a black-list of trouble-makers. As the Enrages paraded through the hall of the sociology building with placards displaying blown-up pictures of alleged plain-clothes policemen, one of the staff complained and tried to enforce the college ban on political demonstrations. There was a scuffle and the dean called the police. Within an hour 4 truck loads of CRS were let into the university by the dean. The Enrages shouted abuse and threw missiles at them, luring them into the university so everybody could see that the police were no longer a rumour but fact, and moderate students joined in to drive the police out of Nanterre. Provocation had drawn repression, which in turn had rallied mass support; it was a classic Situationist victory.

After a series of anti-Vietnam war bomb attacks in Paris, 5 members of the National Committee for Vietnam were arrested. On March 22, as a protest against the arrests, a group of Enrages and Vietnam demonstrators occupied the administration offices at Nanterre and formed the Movement of March 22 (from which the Enrages were almost immediately excluded over accusations of looting). Dany Cohn-Bendit soon established himself as the principal spokesman, describing himself as ‘a megaphone’ for the movement and ‘an anarchist by negation.’ Cohn-Bendit and the Enrages wanted a federal organisation of workers’ councils, who acted together but preserved their autonomy. At Nanterre the threat of the March 22 Movement developed into what the dean described as “a real war psychosis”, the university was closed and Cohn-Bendit and his co-horts were summoned before a disciplinary tribunal.

On May 3 hundreds of left wing students gathered at the Sorbonne, the originally overcrowded university in Paris, to protest. The rector of the university became worried, especially when he heard that right-wing students were gathering nearby, and called the Minister of Education. In spite of what happened at Nanterre, they decided to bring in the police. As students were bundled into police trucks, the assembled crowd started jeering and a stone was thrown through the windscreen of a truck hitting one of the police. Then the students surged forward and tried to liberate their comrades. Tear gas was fired and the violence escalated; the CRS beating innocent bystanders and street fighters alike; the students setting light to cars and tearing up paving stones to hurl at the police.

The rioting spread throughout the Latin Quarter and at the end of the first day around 600 people had been arrested and hundreds more injured. The authorities’ heavy handling of the situation had provided thousands of young Parisians with something concrete to release their pent-up frustration on. On May 6, 20,000 students marched through Paris calling for the release of those arrested; up to 450 more arrests were made and many more injuries were sustained. The next day, 50,000 marched to the Arc de Triomphe behind a banner declaring ‘Vive La Commune’, singing ‘The Internationale’. The most fierce street fighting took place on May 10, ‘the night of the barricades’, when the students attempted to drive the CRS from the Latin Quarter. After that Pompidou withdrew the police from the Sorbonne, saying the case of the arrested students would be reconsidered and the university reopened.

As news of the events spread, via TV footage of the burning barricades and street battles, thousands of young people from not just France but all over Europe made for Paris. With ‘What A Wonderful World’ by Louis Armstrong top of the chart, an English student reported in the Solidarity Paris pamphlet: ‘First impression was of a gigantic lid being lifted, pent-up thoughts and aspirations suddenly exploding, on being released from the realm of dreams into the realm of the real and possible. In changing their environment people themselves were changed. Those who had never dared to say anything before suddenly felt their thoughts to be the most important thing in the world and said so. The helpless and isolated suddenly discovered that collective power lay in their hands… People just went up and talked to one another without a trace of self-consciousness. This state of euphoria lasted throughout the whole fortnight I was there.’

The walls of the Latin Quarter were covered in graffiti and flyposters declaring: ‘Be realistic demand the impossible’, ‘Take your desires for reality’, ‘It is forbidden to forbid’, ‘The more you consume the less you live’, ‘Long live communication, down with telecommunication’, ‘The commodity is the opium of the people’, ‘Culture is the inversion of life’, ‘Go and die in Naples with Club Mediterranean’, ‘They are buying your happiness, steal it’, ‘Refuse your assigned roles’, ‘Live without restrictions or dead time’, ‘Knowledge is inseparable from the use to which you put it be cruel’, ‘Scream, steal, ejaculate your desires’, ‘Art is dead: Do not consume its corpse’, ‘Even if God existed we would have to suppress him.’

At the Centre Censier the Situationists and Enrages formed the Council for the Maintenance of the Occupations and set up worker/student action committees to run the sit-ins and strikes that were spreading throughout France. On May 17 they sent a telegram to China: ‘Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party, Gate of Celestial Peace, Peking. Shake in your shoes bureaucrats, the international power of the workers councils will soon wipe you out. Humanity will only be happy the day that the last bureaucrat is strung up by the guts of the last capitalist. Long live the factory occupations. Long live the great Chinese proletarian revolution of 1927 betrayed by the Stalinists. Long live the proletariat of Canton and elsewhere who took up arms against the so called popular army. Long live the workers and students of China who attacked the so called cultural revolution and the bureaucratic Maoist order. Long live revolutionary Marxism. Down with the state. Occupation Committee of the Autonomous and Popular Sorbonne.’

By May 21, up to 10 million French workers were on strike, around half the workforce, most factories were occupied, the French transport system had come to a standstill, and everybody from footballers to film directors were supporting the students. The Situationists and the Enrages at the Centre Censier endlessly produced leaflets on self-management and workers’ councils, whilst, at the same time, denouncing the Communist Party and the CGT for trying to take the credit and manipulate things for their own party political ends. On May 28 de Gaulle secretly flew to West Germany, where General Massu, the commander of the French army, was stationed on NATO exercises. The following day he returned to Paris with Massu’s assurance that the army was still loyal enough to support him in any confrontation. First he called Pompidou and the cabinet to tell them he was going to dissolve the National Assembly and call an election. Then he addressed the nation, announcing that the country was threatened by a ‘communist dictatorship’ and that, if necessary, he would have no hesitation in calling in the army.

The communist threat was all that was needed to whip up enough patriotic fervour to get the centre to join with the right and recuperate the situation. In the elections that followed de Gaulle was returned to power by the biggest majority in French history. Despite the millions on strike and hundreds of thousands on the streets, the student movement was basically the work of an intellectual elite and at the end of the day the majority could not be lured away from the capitalist carrot. The workers could not understand the intellectual repression felt by the students and their theories were all so much idle rubbish compared with the day to day reality of earning a crust. But the students had succeeded in bringing out the discontent in French society, if not the world, at the ever increasing distance between the bureaucrats and those whose lives they control; as well as the redundancy of traditional left wing parties.

The Situationist International, which had already split in 2, was further decimated by various expulsions, resignations and scissions until its eventual demise in 1972. Or was it a CIA black op? According to New Solidarity, the paper of the US National Caucus of Labour Committees: ‘The Makhnist Situationist International pig countergang created by the CIA from scratch in 1957 in France under the slogans ‘Kill the vanguards’, ‘Workers’ councils now’ and ‘Create situations’ is the paradigm example of a CIA synthetic all-purpose formation. The loose and programless anarchist ‘left cover’ countergang of the SI model is ideal for the CIA for the recruitment of new agents, the launching of psywar operations, the detonation of riots, syndicalist workers’ actions, student power revolts, etc, the continual generation of new countergang formations, and infiltration, penetration and dissolution of socialist and other workers’ organisations… During the 1968 French general strike the Situationists united with Daniel Cohn-Bendit and his anarchist thugs in preventing any potential vanguard from assuming leadership of the strike – thus guaranteeing its defeat.’

Another Situationist critic, Heathcote Williams wrote in International Times in 1977 that ‘Paris ’68 was rich in nameless wildness, but it was marred by a small group of embittered scene-creamers, who called themselves Situationists, and who tried in typically French fashion to intellectualise the whole mood out of existence, and with their very name tried to colonise it. Failed activists and mini-Mansonettes who boasted that all their books and pamphlets (Leaving the 20th Century, The Veritable Split in the 4th International, etc) had been produced from the proceeds of a bank robbery when even the most lavish of them could have been produced for the price of a few tins of cat food from Safeways (one tiny exception being Ten Days That Shook the University by Omar Khayatti)… Their heroes are a legion of mad bombers: Ravachol, Valerie Solanas, Nechayev, the IRA, et al.’

London 1968 ‘People who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal or constraints, such people have a corpse in their mouth.’ Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life

In the wake of the March anti-Vietnam war demo in Grosvenor Square, a group of Vietnam protesters turned up at a Notting Hill People’s Association meeting in All Saints church hall on Powis Gardens, intent on more local radical action. The Hustler underground paper reported that ‘various opinions at the meeting made for a vigorous, occasionally explosive atmosphere… from raffles to revolution… forcibly open the garden squares, resist rent rises, set up an alternative local government, encourage housing associations, set up a co-operative community bank – all were suggested. “It’s time,” said one man, “we started a revolution in North Kensington.”

After several children were run over in the area, a series of People’s Association demos culminated in a local mothers’ march. As the demonstrators made their way around the Powis and Colville squares’ block, the march was diverted by the Vietnam protesters (who were disguised as pantomime animals for the occasion) towards the gates of the Powis Square gardens, which were duly forced open. The May ’68 revolution in Notting Hill may have been overshadowed somewhat by the events in Paris, but one square at least was opened permanently for the people in London. The Council subsequently acquired the gardens from the private owners and eventually converted the area into a children’s playground. As Jan O’Malley put it in The Politics of Community Action, ‘whereas the violent action of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign compelled the Council to capitulate and buy the square, forcing a rapid shift in the situation, the task of generating adequate financing of the square by the Council has been a much more protracted up-hill struggle.’

Apart from the playgrounds, law centres and crèches (what have the hippies done for us?), the most enduring legacy of the Notting Hill ’68 student revolution was the graffiti. The writing on the walls, largely attributed to the post-Situationist King Mob group, included quotes from William Blake, Coleridge and Shelley. Blake’s ‘The tigers (tygers) of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction’ on Basing Street (on the north-east side of the Lancaster Road junction) was tagged with ‘Rent revolt’ and ‘QPR Loft End agro’, and used as a Cat Stevens pose location. ‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom’ in Powis Square was reputedly changed to ‘Willesden’. Coleridge’s ‘A grief without a pang, void, dark, dreer, a stifled, drowsy unimpassioned greif (sic)’ from ‘Ode to Dejection’ on Moorhouse Road was accompanied by ‘Hashish is the Opium of the people’. According to Michael Horovitz, this was painted over and replaced by ‘Look the wall is white again’. Shelley’s ‘Asses, swine, have litter spread and with fitting food are fed, all things have a home but one – thou, oh Englishman hast none’ left little room for more to be sprayed.

On Portobello Road, King Mob signalled the end of peace and love with ‘Burn it all down’, ‘Dynamite is freedom’ and the anti-Beatles ‘All you need is dynamite’ by Melissa’s Café at the Tavistock Road junction (where the 1966 London Free School fair procession began with children singing ‘Yellow Submarine’). This graffiti illustrates the Notting Hill ‘Interzone’ International Times and the Michael X pages in the Some of IT book. Around the Powis and Colville squares there was the somewhat overstated overcrowding protest, ‘Belsen lives’ on Talbot Toad, on the east corner of Colville Gardens; ‘Religion = opium’ on All Saints church; ‘Rachman was right’ on Colville Terrace; ‘Kars kill’ on the corner of All Saints and Westbourne Park Road, ‘The only race is the rat race’ and ‘Revolution Now’. ‘Christie lives’ and/or ‘Remember Christie’ appeared around Rillington Place, and, most memorably, hoardings beneath the Westway flyover, alongside the tubeline between Ladbroke Grove and Westbourne Park, were emblazoned with: ‘Same thing day after day – Tube – Work – Diner (sic) – Work – Tube – Armchair – TV – Sleep – Tube – Work – How much more can you take – One in ten go mad – One in five cracks up.’

In the late 60s, Alex Trocchi was succeeded as the leading British Situationist by Chris Gray, the editor of King Mob Echo who lived on Cambridge Gardens. The IT editor John Hopkins remembers Gray “behaving critically” and “making a dent in the consciousness.” At the time of Trocchi’s Project Sigma, he published the Situationist Totality for the Kids from Hereford Road, and the radical pop pamphlet Heatwave with Charlie Radcliffe. But in 1967 the British Situationists split with the Paris politburo; officially because they sided with the New York yippies against the European intellectuals. However, Fred Vermorel attributes it to the Situationist supremo Guy Debord visiting Notting Hill and finding Chris Gray’s urban guerrilla forces (the Wise brothers) watching Match of the Day.

Fred Vermorel also credits Chris Gray with the proto-punk rock ‘unpleasant pop group’ idea: ‘If the Sex Pistols stemmed from the Situationist International, their particular twist of radical flash and burlesque rage was also mediated through a band of hooligan pedants based in the Notting Hill Gate area of London. This was King Mob.’ Although it can be argued that Mick Farren was already putting the idea into practice with the Social Deviants. When Malcolm McLaren was a radical art student follower of the Situationists his girlfriend Viv Westwood was selling hippy jewellery on Portobello market to support him.

According to The End of Music punk and reggae critique by Dave Wise, the name King Mob came from graffiti daubed on Newgate prison as it was stormed in the Gordon riots of 1780. In Once Upon A Time there was a place called Notting Hill Gate, the Wise brothers noted that the Notting Hill graffiti predated the slogans of Paris 1968, but had to admit they didn’t have quite the same effect. They also disassociated King Mob and the Situationists from later Heathcote Williams material, like ‘Princess Anne is already married to Valerie Singleton’, and music business promotions like the Stones’ ‘It’s Only Rock’n’roll’ (on the Free Shop sign on Acklam Road), whilst distancing themselves from some of King Mob’s more nihilistic plans like hanging peacocks in Holland Park.

Mostly through the graffiti, the influence of the Situationists’ Society of the Spectacle and Revolution of Everyday Life on the hippy movement rivalled that of the beat generation. However, the Wise brothers dismissed the underground scene as ‘just another range of consumer goods, of articles whose non-participatory consumption follows the same rules in Betsy-Coed as in Notting Hill.’ In Days in the Life, Dick Pountain recalls how King Mob used to “terrorise” the IT office with their critical posters. On the first anti-Vietnam war demo, they were renowned for disrupting the Trotskyite chant of ‘Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh’ with ‘Hot chocolate, drinking chocolate.’

In May ’68, as students took to the barricades in Paris, John Hopkins came up with International Times 30, the Notting Hill ‘Interzone A’ map issue; inspired by a combination of William Blake and William Burroughs, the Situationist theory of psychogeography and local history. The ‘Interzone’ IT cover features a Ladbroke Grove Carnival procession cut-up collage by Miles, incorporating some of the Coleridge King Mob graffiti. Courtney Tulloch’s local history is illustrated by the King Mob ‘Dynamite is Freedom’ graffiti, a plan for the Westway Theatre, and ads for Hustler, the Word printers and the Family Dog shop (‘posters, pipes, rings, skins and things’) at 2 Blenheim Crescent. The fold-out and fill-in map, ordained with ‘God gave the land to the people’, became a fixture on most Notting Hill hippy pad walls.

Hoppy recalls Interzone IT as a cross between a marketing exercise and a revolutionary strategy: “I got all the data together from street sellers, the guy doing distribution and postal subscriptions, and plotted it all out on a map, and what I discovered was the main density of people in those days was like a fertile crescent. It followed the 31 bus route that runs down to World’s End, Chelsea, and came up through Kensington and Notting Hill to Swiss Cottage and Chalk Farm. We called it the fertile crescent, which is a phrase from archaeology, from Mesopotamia, and the centre of gravity of IT was in Notting Hill. One of the things we understood then is if you want to take the territory you publish the map, that’s an axiom that really works. So we decided that the first place that we want to conceptually seize is Notting Hill – this is in 1968 – so we published a map and we called it ‘Interzone A’.

“Somebody did some research about the 3 villages, Notting Dale, Westbourne Park and Portobello. The idea wasn’t local history, although I think you can call it that. What we tried to do was provide that information for people, so that they’d know when you walk along the street you’re treading along somewhere people have lived and walked along for hundreds of years. It used to be farms then it was a village. When you stand here imagine that this was a village, trying to help give people a sense of place in time which goes beyond the present. We got some old maps and we traced out the field patterns and we talked to people who reckoned they could remember what their parents and grandparents said going back a hundred years. When you do that your sense of where you are and what you’re walking on changes, it’s like the fields lie dreaming underneath sort of vibe.”

‘Walking the Grove’ in ‘Interzone’ IT, Courtney Tulloch grappled with the paradox of hippy heaven West 11 and concrete island Notting Hell, at one point concluding that ‘Notting Hill in its social aspects – housing and so on – is a huge grimy garbage heap, that is just waiting to get set on fire, like the kids at the adventure playground, and like my own garbage heap at home.’ As the GLC’s car-park plans for the 23 acres under the Westway flyover were discovered, Tulloch thought ‘the area could congeal into a genuinely depressed ghetto, people’s social and economic needs being overshadowed by the gigantic inhuman motorway. This is what happened after the building of over-head railways in Chicago and New York. Local politicians could seize the opportunity to turn Notting Hill into Britain’s first US style black ghetto (if it isn’t that already).’

But, on the other hand, he mused: ‘If the spans are given over to the community, the possibilities for further creative extensions to the children’s adventure playground already under way in Westbourne Park, are total… If you must vote, vote for playspace at the council elections… In the meantime, look forward to the Notting Hill Fair especially, a human bonfire of energy and colour. Don’t wait for the area to change – no change in a physical environment how ever great can ever change you. Instead dig the vibrations in and around Notting Hill, perhaps the only area in London where through the differing enclaves of experimental living, a free-form and ingenious communal life-style could really burst forth… In the 50s most young people who came to Notting Hill were students who only stayed for 6 to 9 months and then moved out. Now there are signs that a real underground community is alive, and especially in the village around Portobello Road, down to the Gate. Each person will carry a fire in their heads despite (perhaps because of) the garbage, the ghetto poverty and the rest.’

As well as his local history walks in IT, Courtney Tulloch edited Hustler, the black underground paper (which preceded Larry Flynt’s porno mag). Hustler covered Council neglect of traffic, housing, poverty, property speculation and the black community, in militant style. The paper’s stark design and attitude resembles a punk fanzine more than a hippy underground paper. The cover of the first ‘What is the Grove?’ May ’68 issue features pictures of an old white man passing a black woman and kids by the ‘Belsen Lives’ graffiti on Colville Gardens, black girls by the ‘Dynamite is Freedom’ graffiti, black and white kids, a nun, hippies/beatniks on Talbot Road, and an old market trader.

Answers to ‘What is The Grove?’ included: ‘The Grove’s just much groovier, way ahead of other areas… A square mile of squalor… A nice homey area, but needs cleaning up… A social dustbin (The Times)… Our own Notting Hill, signs of a real underground community (International Times)… A really dirty area, rats, bad housing, nothing for the kids… The streets are too bumpy and you can’t rollerskate… Notting Hill and North Kensington – areas of anarchy and flux… A splendid sleaziness, of the sort the British like to think of as Mediterranean… A transit area for vagrants, gypsies and casual workers… It’s the sort of place where you have to be because you can’t be anywhere else.’

The first issue contains pictures of Paris style stencil graffiti proclaiming ‘The People’s Centre All Saints Church Hall – Let kids play on the squares’, the Powis Square ‘Trespassers will be prosecuted’ sign, and children playing in the road. The features include ‘Ghetto Control’, ‘Who controls Notting Hill’, ‘Who Knocks Enoch?’, ‘James Baldwin: The Black Experience’, ‘Demonstration Gear American Style’ ’68 fashion, ‘Watts ’65’ on ‘black anarchy’ in the LA riot, and ‘Theatre of the Streets’; some anti-Vietnam war street theatre in St Stephen’s Gardens which sounds like another mini-Carnival. There’s also the first mention of the Mangrove restaurant at 8 All Saints Road.

In the June ‘Tell it like it is’ Hustler there’s a picture captioned ‘The Way to Powis’ of people going through the hole in the square gardens fence. This issue features a ‘Black Power Michael’ book review, ‘People get ready there’s a road coming through’ on the Lancaster West redevelopment, a ‘Know Your Rights’ article on housing law by Bruce Douglas Mann (the future local Labour MP), ‘Black Spirit Sounds’ on the Black Panthers, ‘Powell Power’ and ‘Grove Talk’ on the neo-Nazi Colin Jordan. The November issue, with a Mexico Olympics Black Power salute cover, includes rumours that ‘another fence will soon be enclosing Powis Square’, and one of beautiful black American girls spying on the Notting Hill underground scene. There’s also a review of black community theatre at the ‘Notting Hill Festival’ in September, and ‘The Ghetto Dweller Speaks’ column. As the Powis Square gardens were released from private landlord control, the former Powis Square landlord Michael de Freitas was let out of prison, established as Michael X, Britain’s Malcolm.

Soon after the opening of the gardens, the location was chosen for its ‘kaleidoscopic moods in a strange and faded area of London’, as the setting of ‘Turner’s house’ in Performance. The Notting Hill film, defining both Heaven W11 and Notting Hell, was made in the autumn of 1968 (not ’98) by Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg; starring the most notorious local film address, apart from 10 Rillington Place, ‘81’ (really 25) Powis Square. Leading the supporting cast, Mick Jagger sold his soul to satin as the jaded rock star Turner. His gangster alter-ego Chas (James Fox) sums up the ‘bohemian atmosphere’ of the 1968 Notting Hill scene thus: “What a freakshow, out on the left (either meaning left on the map, left bank, or better left unsaid), it’s a right piss hole, long hair, beatniks, druggers, free love, foreigners.”

In Peter Playdon’s definitive study of Performance, ‘Chas’s journey, through first urban, and then psychic, space, can be read as a process of politicisation, and reflects the transformation of ‘the personal’ into ‘the political’ that saw the rise of Black Power, and the shift from the outwardly respectable but inwardly subversive mod attitude to that of the dissident freak.’ With his identity crisis complete, Fox/Jagger, as Chas/Turner, walks out of 25 Powis Square to John Lennon’s awaiting Rolls, and the 60s were over – bar a bit more chanting and protesting.

25 (‘81’) Powis Square wasn’t a Rachman house, in spite of being in the heart of his slum empire, but would gain further notoriety as an Angry Brigade safehouse and blues party venue, while the square gardens continued to be a focal point of community action. As Jan O’Malley summed up Powis Square playpower in The Politics of Community Action, ‘throughout the long struggle for Powis Square, the square itself has provided a public forum for all kinds of community events – for carnivals, for bonfire parties, for housing rallies, puppet shows and concerts, and so has always been seen and used as much more than a play area.’

In October ’68, as Performance was being filmed, another Notting Hill community campaign was launched in IT 41 by the King Mob group, after 6 of the Powis Square stormers were charged with causing ‘malicious damage’ to the gates. As Russian tanks were quelling the student uprising in Czechoslovakia, King Mob twinned Powis Square with Prague’s Wenceslas Square on their flyer, which reads like a punk gig line-up: ‘Powis (Wenceslas) Square in Notting Hell for the Devils Party – the Damned, the Sick, the Screwed, the Despised, the Thugs, the Drop-outs, the Scared, the Witches, the Workers, the Demons, the Old – give us a hand, otherwise we’ve had it.’

After the attempted assassination of Andy Warhol by the radical performance artist Valerie Solanas, King Mob issued their own hit list in solidarity featuring Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, David Hockney, Miles and Twiggy. The Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren was particularly inspired by their attacks on Wimpy bars on Portobello and Harrow Road, and re-enacted their most famous demo in The Ghosts of Oxford Street film. At Christmas ’68, with one of their number dressed in a red coat and white beard, a King Mob group went into Selfridges on Oxford Street and proceeded to give away presents to children; until the police were forced to arrest Santa Claus. The following year, they presented a ‘Miss Notting Hill ’69’ Carnival float, featuring a girl with a giant syringe attached to her arm: ‘A comment on the fact that there was junk and junk, the hard stuff, or the heroin of mindless routine and consumption.’

The community revolution in Notting Hill in the late 60s was best summed up by Bob Marsden in his Play Association History, as a Chestertonesque struggle between the south and north of Kensington: ‘The real opposition is not between alternative rational means of organising play provision, but between the different ideologies, moralities, ambitions, strategies and tactical styles of the two Kensington communities, as they are played out in that charitable buffer zone which has for so long protected the rich and cheated the poor. Now a situation had arisen where the buffer zone had been occupied and used as a strike base by the agents of the poorer. This constituted a real threat to the power and security of the otherwise impregnable Council establishment. Their hitherto successful strategy of control by neglect no longer worked, and only some kind of direct counter-action could now control the plague of anarchy and revolution which they imagined to be sweeping over the north of the borough.’